Expulsion – 90 Day Notice

Background to Catastrophe

Newly independent Tanganyika (1961), Uganda (1962) and Kenya (1963) introduced ‘Africanisation’ policies to give more power to native Africans. Asians felt threatened and some moved to Britain, India, or Pakistan.

The ‘Kenyan Asian Crisis’

In 1968 the British Labour government decided to change the Act under which holders of British Colony passports (link to 2.4.2 – British Passports, by Prof Bernard Ryan. To follow) could move to Britain. Numbers moving to Britain from Kenya soared to 1,000 a month in early 1968, to beat any ban.

Banished

In Uganda, President Milton Obote accused Asians of greed, cheating, failing to integrate, disloyalty and plotting against Uganda.

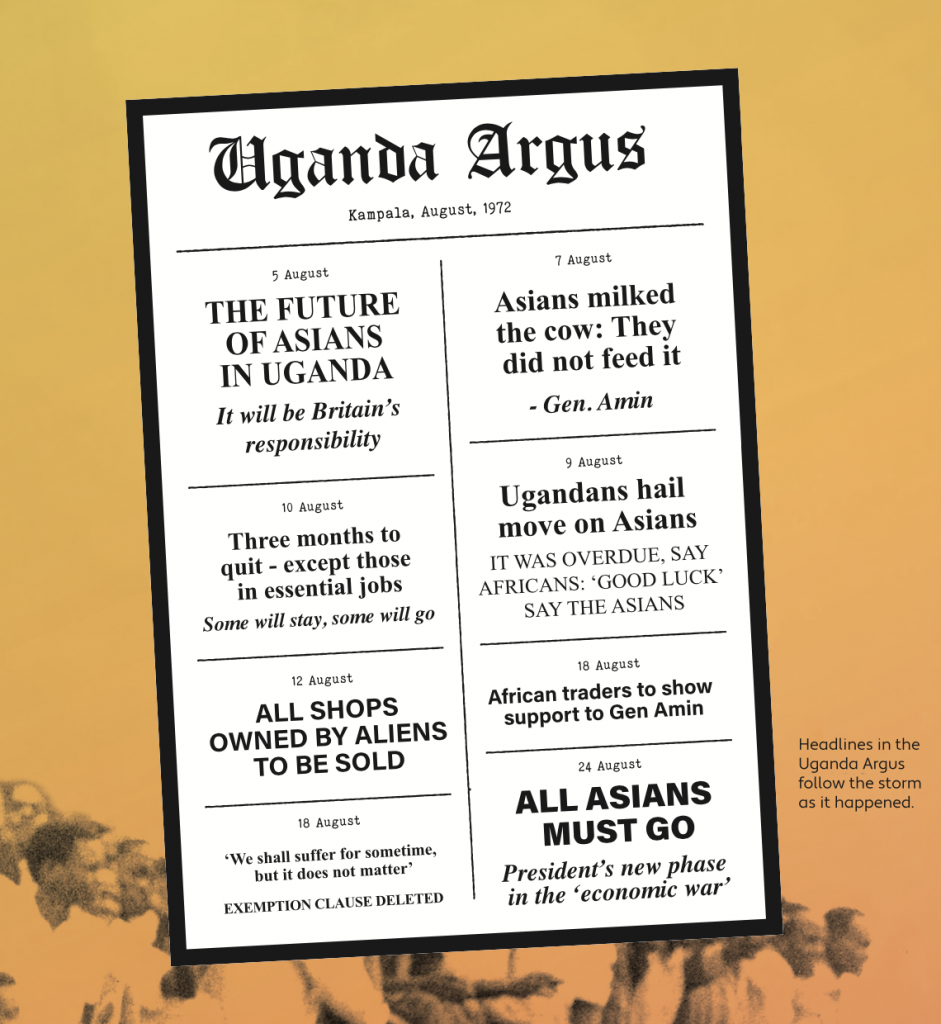

Then, in 1971, the head of the army, General Idi Amin, seized power. When this happened, many Ugandan Asians hoped Amin would be more supportive of them than Obote. But on the 4th August 1972 Amin announced that all Asians without Ugandan citizenship must leave the country within 90 days. As news of violence against Asians across Uganda spread in the wake of the announcement, shock turned to fear as the reality sank in. It took 10 fearful days for the UK to accept legal responsibility for British passport holders.

Then new announcements from Amin added to the shock when, in mid-August, he announced that the 23,000 Asians with Ugandan passports were also to be expelled, stating that, for those Asians who did not leave “it would be like they are sitting on the fire.”

In response, the United Nations declared that those without national passports were ‘stateless’ and sought countries to accept them. Countries around the world started accepting stateless Ugandan Asians. Thanks to a friendship between the Aga Khan, the spiritual leader of the Ismaili Muslims, and the Canadian Prime Minister, Pierre Trudeau, Canada accepted 6,500 Ugandan Asians, mostly Ismaili Muslims.

Road to Entebbe

Before any Ugandan Asians with British Passports could leave the country, the British government insisted that they needed an ‘entrance certificate’ for each family member in the form of a stamp on their passports. Wherever you lived in Uganda, this involved a trip to the British High Commission in the Ugandan capital, Kampala. Short opening hours and some unhelpful staff meant long queues that stretched out of the building and into the surrounding streets. Despite these long waits in the Ugandan heat and the constant fear of being dragged away by soldiers, the Ugandan Asians did their best to stay calm.

Once the entrance certificates had been obtained, each family member had to carefully choose which personal items to pack in their single small suitcase they could take out of the country. All other possessions, their homes, businesses and cars had to be abandoned. With the equivalent of just £55 per family, Ugandan Asians made their way to Entebbe Airport.

Although only situated 30 miles south of Kampala, the journey to the airport could be both long and harrowing. There was a constant threat of attack by drunken soldiers at check points along the road, looking to steal any valuables the Ugandan Asians had packed. Once at the airport, there was a further gauntlet of searches the travellers had to undergo and, even if their luggage did make it through the checks, there was no guarantee of it being loaded onto the plane.